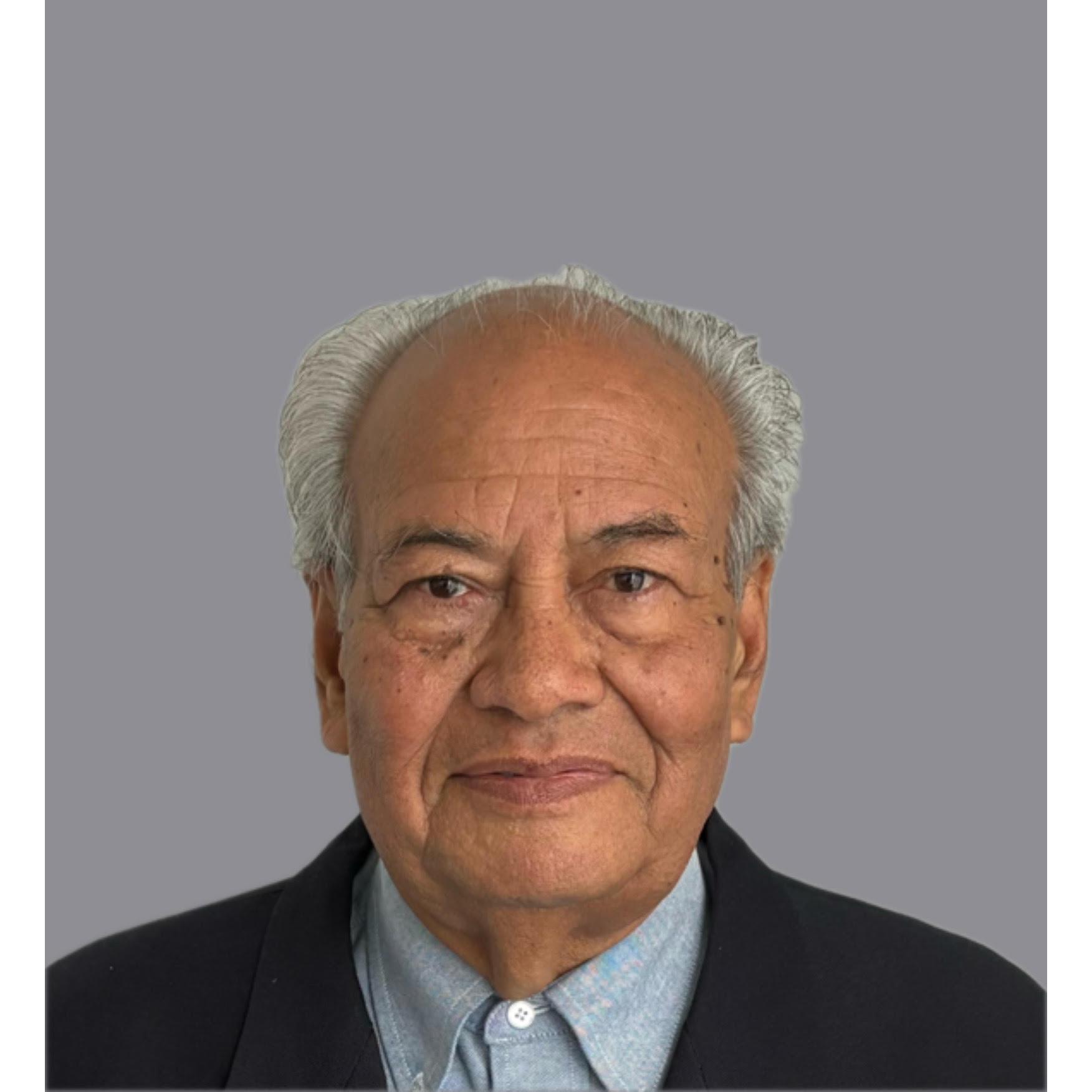

By Narayan Prasad Mishra

According to the Constitution of Nepal, 2015, our country follows a democratic republican federal system of governance. Since its implementation, it is well known that the reins of power have mostly remained in the hands of Nepali Congress President Sher Bahadur Deuba, CPN-UML Chairman Khadga Prasad Oli, and Maoist leader and current Chairman of the Communist Party of Nepali, Pushpa Kamal Dahal “Prachanda.” Primarily, these three leaders have taken turns running the government. Therefore, they deserve credit for all the progress, development, construction, achievements, and advancements made during this period. At the same time, they must also bear responsibility for the destruction, decline, disorder, corruption, irregularities, internal conflicts, misgovernance, nepotism, favoritism, injustice, and oppression that have been evident in the country during the same years. There should be no debate that those who claim credit for progress must also share the blame for decline.

Everyone surely remembers how these three leaders, whenever outside government, accused one another of corruption, misgovernance, irregularities, and causing suffering to helpless citizens. Yet as soon as they received another chance to rule together, they would suddenly see each other as pure and trustworthy, become close allies, and declare that all people were happy and that good governance had been established. This, too, remains fresh in everyone’s mind.

Just as everyone feels the heat in summer and the cold in winter, everyone experiences the effects of the governance system. No one needs to be reminded of its joys or sorrows—everyone is a sufferer or a beneficiary. Whatever good or bad has happened, the people know it themselves. To speak honestly—with God as witness, according to our cultural values—there are two kinds of people in our country: the privileged and the suffering. Because party-based governments prioritized their own parties and cadres over the nation and its citizens, a small group, closely aligned with the ruling parties, became privileged, while the rest suffered. The privileged often viewed good governance as beneficial because they personally benefited from it. The suffering majority, deprived of any share, saw only disorder and misgovernance. This is the true state of the country as I have seen and experienced it.

On Bhadra 23 and 24 (September 8 and 9), a sudden, unexpected, massive nationwide movement erupted under the leadership and participation of very young members of the generation calling itself Gen Z. This movement rose against corruption, disorder, and misgovernance, and in favor of establishing the rule of law and good governance. It shook the mighty, nearly two-thirds majority coalition government to its core, uprooting it within roughly 27 hours like a violent storm or cyclone. Regardless of the name “Gen Z,” I believe this was ultimately a movement of the suffering majority against the privileged minority. Gen Z youths came to the streets, and the rest of the suffering public stood with them. The same three political parties—who become close allies when in power but bitter enemies when out of it—also seized the moment to destroy one another, joining the turmoil. Loss of life, property, and national assets occurred within hours, on a scale rarely witnessed anywhere in the world. Seeing the homes of powerful leaders—who had long enjoyed status, luxury, and authority—damaged, burned, and destroyed, one cannot deny that this was a revolt of the suffering against the privileged.

As a result of the rebels’ demands and recommendations, a neutral government led by Prime Minister Sushila Karki has been formed. It is considered neutral because no political party is visibly represented in it. Its term is only six months, and its primary mandate appears to be dissolving the old House of Representatives and holding new elections on Falgun 21 (March 5, 2026). Therefore, it is doubtful that this government will be able to control corruption or establish effective governance in a meaningful way within such a short time. Thus, this movement—like a sudden storm—may disappear from the Nepali sky without leaving any significant achievement for the people or the nation.

On the other hand, the Gen Z group—initially appearing as a united force representing the collective interests of the country’s suffering majority—has now scattered into various ideological camps: Maoist, royalist, democratic, socialist, and others, drifting away from its original character and purpose. The people who stood against those parties during the time of revolution, surprisingly, became an integral part of the same parties. This has cast serious doubt on its continued existence. If this trend continues, the Gen Z movement will fade away like smoke, dust, or fog, leaving no lasting impact on the country’s development or the welfare of its people.

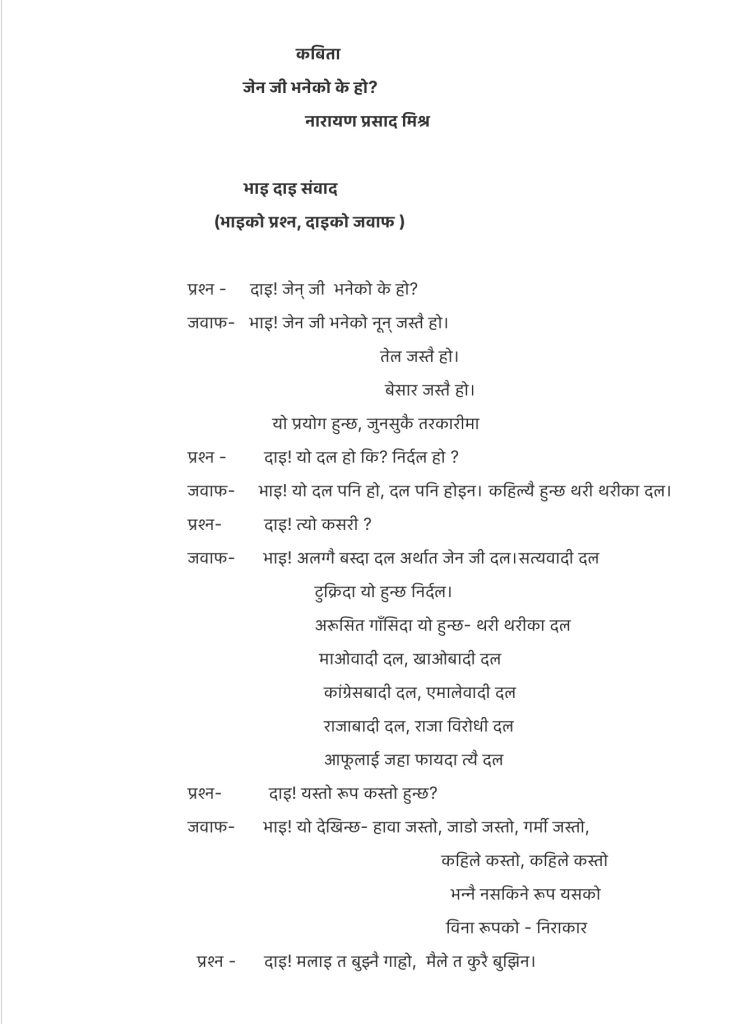

With this concern in mind, my poem—a dialogue between two brothers, the elder and the younger, about Gen Z—was published in the Gorkha Express weekly on Nov. 29, 2025 (Mangsir 13, 2082). The poem in Nepali, along with its English translation, is given below.

Poem in Nepal

Poem Translated into English

What is Gen Z?

Narayan Prasad Mishra

Dialogue Between Younger Brother and Elder Brother

(Younger brother’s questions, elder brother’s answers)

Question — Brother! What is Gen Z?

Answer — Brother! Gen Z is like salt,

like oil,

like turmeric—

something that finds its way

into every kind of vegetable.

Question — Brother! Is it a party? Or a non-party?

Answer — Brother! It is a party, and also not a party.

At times, it becomes all sorts of parties.

Question — Brother! How is that possible?

Answer — Brother! When it stands alone, it is a party—

The Gen Z Party: a truthful party.

When it breaks apart,

It becomes non-party.

When it joins with others,

It turns into many kinds of parties:

the Maoist Party, the Looters’ Party

the Congress-based Party, the UML-based Party,

the Monarchist Party, the Anti-Monarchist Party,

The party that serves its own gain.

Question — Brother! What does such a form look like?

Answer — Brother! It looks—

like the wind,

like the cold,

like the heat—

like this and like that.

Shapeless, without any form.

Question — Brother! It is so difficult to understand.

I still can’t quite understand it.

Note — This poem is translated into English based on the above Nepali poem, not translated word-for-word.

Although the Gen Z movement led to significant personal and national losses, it also ignited hope in the hearts of citizens who had long been oppressed by partisan interests and disorder—hope that perhaps now there might be justice, equality, and good governance. This hope seems, in a way, to have already put on the clothing of despair. How many people are still left in the country who are committed to keeping this hope alive—very few, or perhaps none at all? Only the future will reveal that.

Comments:

Leave a Reply