By Our Reporter

The argument over a revision to the cooling-off period clause in Nepal's Federal Civil Service Bill is more than just a legal error. It demonstrates that powerful figures in politics and the bureaucracy are collaborating to protect their own interests at the expense of clarifying the law and keeping citizens accountable. The subsequent parliamentary probe revealed that there was more than just a typographical error. It was clear that the legal language had been modified to make a provision intended to prevent senior officials from immediately moving into important government positions when they retired less effective.

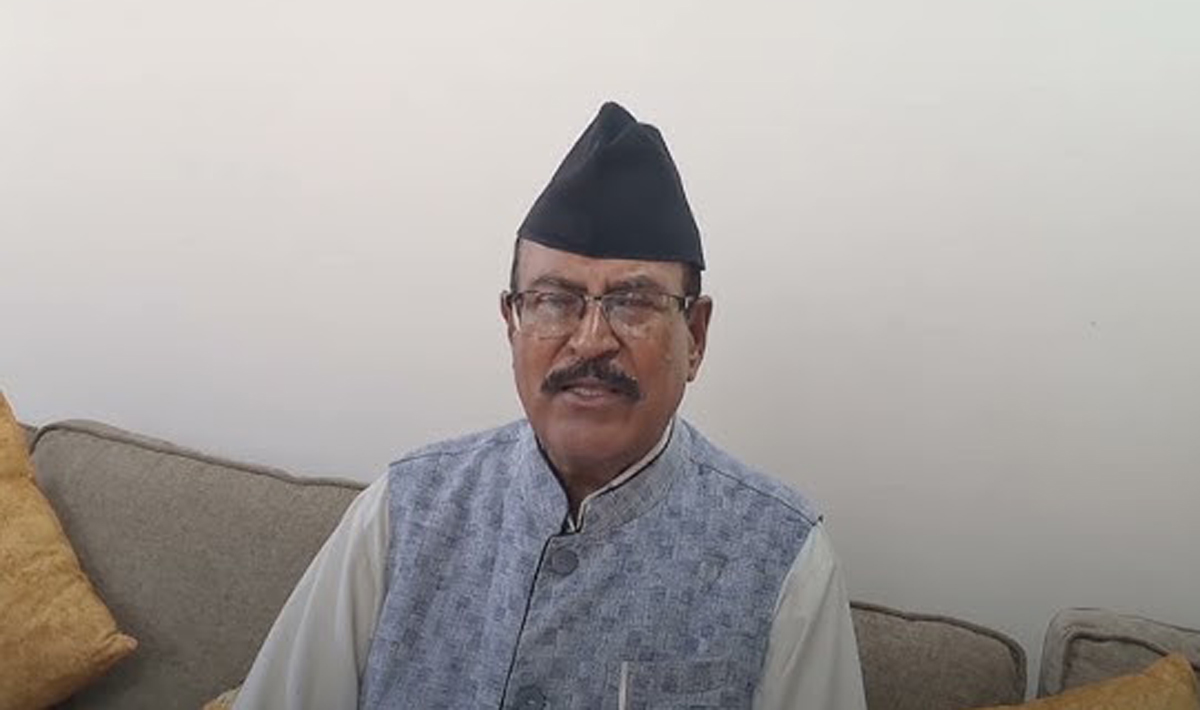

Ramhari Khatiwada, a Nepali Congress member who headed the State Affairs and Good Governance Committee, is at the center of the scandal. His signature was on the incorrect report forwarded to the House of Representatives. According to the committee's investigation, Khatiwada is now morally culpable. However, he was not the only one. The study also blames Chief Secretary Ek Narayan Aryal, Federal Parliament Secretary General Padma Prasad Pandey, and other senior officials for failing to meet expectations.

The trouble began when Clause 82 of the statute, voted by the House on 15 Ashar, included two sub-clauses that were unclear. Sub-clause 4 made it clear that no civil worker who resigned or retired could be nominated for a government or constitutional position for two years. However, Sub-clause 5 included ambiguous exceptions for people retiring from gazetted special or first-class positions, leaving room for conflicting interpretations. That contradiction was not accidental. It appeared to be meticulously crafted so that high-ranking officials, such as secretaries and joint secretaries, could completely bypass the cooling-off period.

There is a clear reason for this action. In Nepal, the close nexus between retired officials and politicians contribute significantly to the country's governance issues. Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli and several of his party members showed dislike to cooling-off provision. They wanted to remove it from the bill while the Congress, the Maoist Centre and fringe parties had advocated for it. Many government employees, even as they prepare to retire, build networks with ministers and party leaders to ensure they land in critical posts, whether in constitutional bodies, diplomatic offices, or development projects. A forced two-year wait would disrupt this long-standing exchange of favors. So, it is not unexpected that some high-ranking officials perceived the cooling-off period provision as a threat to their post-retirement plans and sought ways to circumvent it.

The report is unequivocal in stating that if everyone involved had done their jobs properly, the event would not have occurred. While the chief secretary's name was not specifically specified in the results, his responsibilities were clearly defined. The Secretary General of Parliament also acted in a manner that did not reflect the integrity required of someone in that position. When officials and politicians cooperate in this way, it raises serious concerns about legislative integrity and administrative ethics.

It's more than simply one clause or bill. This case exemplifies a larger pattern in which individuals in positions of authority violate the law for personal advantage. The fact that the term was changed during discussions and passed despite its contradicting wording suggests that numerous eyes were intentionally closed. Only after public outcry and mounting criticism was the House forced to form a special seven-member committee to investigate the issue.

This committee, chaired by Congress MP Jeevan Pariyar and comprised of leaders from all major parties, worked beyond its specified deadline and unanimously agreed that accountability must be accepted and implemented. The level of cross-party agreement demonstrates how unjustifiable the manipulation was.

In his defense, Khatiwada stated during a news conference prior to the committee's formation that he was willing to accept whatever consequences. That may sound like accountability, but moral responsibility rarely leads to political consequences in Nepal's political culture. The actual test will be whether this study results in any changes in how laws are digested and analyzed, or if it is simply another paper that is shelved after a brief news cycle.

This instance has demonstrated that Nepal's problem is not only with corrupt people, but also with a system that encourages and rewards such behavior. If retired officials may fiddle with legislation to fit their own desires and incur no consequences, public trust in governance erodes further. At a time when public trust in institutions is already low, these backdoor efforts exacerbate the perception of impunity that has persisted in both politics and bureaucracy.

Fixing this will require more than committee reports. It is necessary to ensure accountability, not only morally but legally. Otherwise, we are only a few signatures away from weakening the very norms that are designed to ensure fairness in public service.

Comments:

Leave a Reply